|

Evolution and DomesticationFour years of hard work, almost 4000 genomes - the fruit of this effort has now been published in Science. The Wild Grapevine Collection of the KIT had an important role here. It could be shown that Grapevine was domesticated twice independently, once in the Caucasus to produce wine, a second time in the Near East to get table grapes. During its migration to the West, there were numerous love affairs with local wild grapevines, giving rise to the large diversity of grapevines. This project joined people from 16 countries, despite sometimes difficult political circumstances and allows a deep look into the complex history of this crop plant that not only founded civilisations, but was also one of the first globally traded goods, breaching the borders of geography, language, and religion. The treasure of knowledge generated in this project has not even been scratched - during the time, when grapevine, by an interplay between climatic disruptions and human migration, conquered many regions, it collected genes that help to cope with adverse conditions. These genes can help now to safeguard viticulture against the consequences of climate change - this is exactly, what we do now in our Interreg Upper Rhine project Kliwiresse. Seminar as part of the Saturday University Freiburg.

Science article Interview with the Washington Post Youtube on the impact of the project for the region

|

||

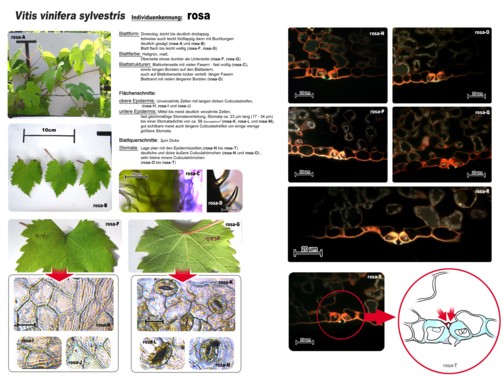

The European Wild Grape (Vitis sylvestris)

The European Wild Grape (Vitis sylvestris) is the ancestor of our cultivated Grapevine. This Crop Wild Relative has survived the ice age in small refugia in the delta of Rhone and Danube and from there moved back along with the expanding alluvial forests through the entire Europe. Our cultivated Grapevine originated around 8000 years in Georgia from the European Wild Grape and spread later, along with the first biotechnological invention of mankind, winery, from East to West and has, during this migration accepted genes from Vitis sylvestris, its wild ancestor.

When from the 19. century the large streams were progressively regulated and therefore the natural alluvial forests disappeared, this eliminated also the Wild European Grape. Meanwhile, this species has moved to the verge of extinction. In many European countries it has already got extinct. One of the largest natural populations still survived on the Ketsch peninsula near Karlsruhe. In addition, single individuals have survived in the alluvial forests along Rhine, Rhone and Danube. These last Mohicans are not only endangered by imbreeding - many of these plants even fail to find a mating partner. The European Wild Grape is diecious, there are male and female plants (very seldom also hermaphrodites). In addition, the species is endangered by genetic introgression - Rhine, Rhone and Danube pass large viticultural areas and wild grapes could hybridise with cultivated grapes. Even worse: rootstocks of North American grapes that are used in viticulture to contain Phylloxera can be drifted into the large rivers from abandoned vineyards and invade the alluvial forest, where they spread as so called neophytes and bastardise with our native European Wild Grape.

Due to this extremely dramatic situation, ex-situ conservation is a mean of choice. In a project funded by the Federal Office for Food and Agriculture (BLE) we have, in cooperation with the Aueninstitut in Rastatt mapped the last survivors in Ketsch and other sites of the Rhine valley, generated cuttings and propagated those in the Botanical Garden. These cuttings have now been brought back in several planting campaigns to promising sites of the alluvial forest. To ensure natural gene flow, genetically different individuals are planted together in patches. As precondition, we have investigated the genetic relationship based on paternity assays (using so called microsatellite markers).

Goal of the project is to enable the European Wild Grape to establish a sustainable population in the Upper Rhine Valley.

This conservation project led to an unexpected side effect. During more detailed analysis of the wild Grapes many of them turned out to be resistant against important diseases such as Downy Mildew, Powdery Mildew, or Black Rot. Even against the novel Esca disease that spreads now in consequence of global warming, some of them were resistant. Meanwhile we have established in the Botanical Garden a complete genetic copy of the German Wild European Grape and we have started now in the context of two funded projects, to exploit this valuable genetic ressource for sustainable viticulture.

This example demonstrates very clearly that conservation of biodiversity is of practical value for mankind. more...